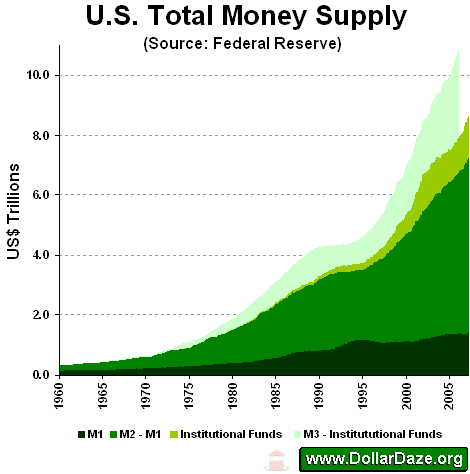

The money supply represents the total amount of a currency that is circulating through the economy.

That may seem like a strange concept, but in this day and age of fiat currencies (currencies that are not backed by any physical asset, such as gold) and computers, the supply of any given currency can change in literally less than a second.

No longer do government treasuries have to fire up the printing presses to increase the supply of money, although they can still do that if they want to. Nowadays, the same thing can be accomplished with a few keystrokes on a computer.

The supply of money in the economy is important to us as currency traders because it has a direct impact on the value of a currency. More money in circulation tends to lead to lower currency values, while less money in circulation tends to lead to higher currency values.

The money supply in a given country is typically dictated by:

- The government’s Treasury

- The country’s central bank

Role of the Treasury in Determining the Money Supply

As we mentioned previously, the Treasury typically controls the printing presses at the mint. And since fiat currencies aren’t backed by any physical asset, all the Treasury has to do to increase the money supply is place an order for paper (or cotton, as is the case in the United States) and ink and turn on the presses.

As these new bills are distributed into the economy, the supply of money increases.

Of course, if these new bills are being created to replace old, tattered bills that are going to be collected and destroyed once the new bills are distributed, the supply of physical money in the marketplace will remain unchanged.

However, the important thing to remember here is just how easy it is to flip a switch and start printing.

Role of the Central Bank in Determining Money Supply

As easy as it may be to flip a switch and start printing, it is even easier for a central bank to increase or decrease the money supply.

All a central bank has to do to increase or decrease the money supply is type a few numbers into a computer and hit “Enter.”

In fact, central banks engage in the creation and destruction of money every day as they implement their monetary policies. Here are the basics of how central banks affect the money supply.

We’ll use the U.S. central bank the Federal Reserve, or the Fed as an example.

- When the Fed wants to lower interest rates in the economy, it will start to increase the money supply by making short-term collateralized loans (called repurchase agreements, or “repos” for short) to its primary dealers (large banks). In a repo, the Fed borrows U.S. Treasuries from a primary dealer in exchange for crediting the dealer’s reserve account with the Fed. At the end of the term of the repo, the Fed gives the U.S. Treasuries back to the primary dealer and debits the dealer’s reserve account with the Fed.

- When the Fed wants to raise interest rates in the economy, it will start to decrease the money supply by taking short-term collateralized loans (called reverse repurchase agreements, or “reverse repos” for short) from its primary dealers (large banks). In a reverse repo, the Fed lends U.S. Treasuries to the primary dealer in exchange for debiting the dealer’s reserve account with the Fed. At the end of the term of the reverse repo, the Fed takes the U.S. Treasuries back from the primary dealer and credits the dealer’s reserve account with the Fed.

The amazing thing about all of this is that there is no physical creation or destruction of money. It all takes place via a simple computer entry.

The Fed doesn’t have stacks of 100-dollar bills and stacks of U.S. Treasuries sitting around that it distributes back and forth to big banks. All it has are computers and a team of people that make credit and debit entries into accounts.

Of course, as we have seen in the wake of the financial crisis of 2008, the Fed and other central banks aren’t limited to short-term repos or reverse repos when they want to increase the money supply. They can engage in quantitative easing.