Retail traders are speculators. This one is pretty straightforward. You are a retail trader, and let’s face it, you are not getting into the Forex market to hedge your foreign accounts payable exposure, you are not trying to facilitate transactions between institutional traders, and you are definitely not trying to manipulate currency values from within your personal account. You are in the Forex market to make money.

Retail Forex trading activity has grown substantially since 2000. Average daily trading volume on retail Forex platforms (which is somewhere around $118 billion-Forexmagnates.com) is relatively small when compared with total daily Forex volume, but it is a segment that continues to grow.

RETAIL FOREIGN EXCHANGE DEALERS (RFEDS)

Retail foreign exchange dealers (RFEDs)—often referred to as “dealers”—are facilitators and speculators. RFEDs play a key role in the life of any retail trader by providing a conduit into the Forex market. However, their dual roles of facilitator on the one hand and speculator on the other hand have led to some controversy in the market.

RFEDs as Facilitators

If you are a retail trader and you want to trade spot Forex, you need to work with an RFED. Without RFEDs, you would be shut out of the spot Forex market. After all, huge megabanks like Deutsche Bank and UBS aren’t going to give you, as an individual trader, the time of day when it comes to trading currencies. They have much bigger fish to fry.

By aggregating retail traders’ accounts and trade flow, RFEDs are able to establish relationships with big money-center banks and prime brokers, then turn around and share that access with us.

Now, don’t misunderstand that statement. RFEDs don’t give retail traders access to the interbank market by letting them trade directly with banks and other big players in the market. Instead, RFEDs give retail traders access by acting as counterparty to (taking the other side of) all their trades and then turning around and placing their own trades in the interbank market to offset the currency exposure that they have assumed by acting as counter-party for their clients. Here’s how it works.

When a retail trader enters an order to buy 1 EUR/USD contract, she is buying that contract from her RFED. So after this first transaction, the retail trader is long 1 contract on the EUR/USD and the RFED is short 1 contract on the EUR/USD. To eliminate this short exposure to the EUR /USD, the RFED will turn around and buy 1 EUR/USD contract on the interbank market. By holding 1 short EUR/USD contract and 1 long EUR/USD contract, the RFED is able to offset its exposure and risk.

This is a pretty slick system. Retail traders get to place the trades they want, and the RFEDs get to offset their risk. However, this isn’t always the way it happens. RFEDs don’t always offset their risk—which brings us to the concept of RFEDs as speculators.

RFEDs as Speculators

RFEDs speculate in the Forex market by not offsetting all of their clients’ trades.

Going back to the example we just used to illustrate how an RFED can act as a facilitator, recall how the RFED acts as counter-party to the trades that its clients make. This is the service that the RFED provides. However, once a client places a trade, the RFED is under no obligation to offset that trade. So long as the RFED honors the trade with its client, it can choose whether it wants to offset that trade or hold on to it. If the RFED chooses to offset the trade, it puts the trade into its “offset flow,” or “A book,” and proceeds to place a corresponding trade in the interbank market. Conversely, if the RFED chooses not to offset the trade, it puts the trade into its “managed flow portfolio,” or “B book,” and maintains its exposure to the trade.

Offset flow (A book): This is the portion of the RFED’s portfolio that it chooses to offset by placing corresponding trades in the interbank market.

Managed flow portfolio (B book): This is the portion of the RFED’s portfolio that it chooses not to offset in the interbank market.

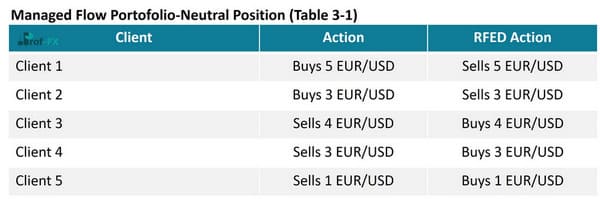

The managed flow portfolio contains trades from many different clients for which the RFED has been the counterparty. In many cases, these trades offset each other naturally, but sometimes they don’t. For instance, you could see the trades in Table 3-1 in the managed flow portfolio.

Looking at the sum of the five actions taken by the RFED, you can see that the RFED is in a net neutral position: it sold 8 EUR/ USD contracts (5 + 3 = 8), but it also bought 8 EUR/USD contracts (4 + 3 + 1 = 8). In this instance, the actions of the RFED’s clients left the RFED in a naturally hedged position.

Now let’s take a look at a slightly different scenario. Imagine that you now see the trades in Table 3-2 in the managed flow portfolio.

Looking at the sum of these five actions taken by the RFED, you can see that the RFED is in a net short position: it sold 15 EUR/ USD contracts (10 + 5 = 15), and it bought only 10 EUR/USD contracts (6 + 3 + 1 = 10). In this instance, the actions of the RFED’s.

Clients left the RFED exposed to price movements in the EUR/ USD goes down, the RFED will make money. If the EUR/ USD goes up, the RFED will lose money.

So by determining which client orders it is going to put in the managed flow portfolio, the RFED gets to decide whether it wants to have long or short exposure to any currency pair.

This concept of offsetting some client transactions while not offsetting others was one that was not widely understood among retail traders (and may still not be), but the curtain was pulled back when companies like Gain Capital Holdings (Forex.com) filed their S-1 documents as they prepared for their initial public offerings (IPOs) on the U.S. stock market.?